” WORDS ARE THE ENEMY OF UNDERSTANDING”

——- Buddhist Saying

@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@

” ALL YOU GET FROM A TUNER IS AN OPINION”

——– Guitarist Leo Kottke

@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@

” WORDS ARE THE ENEMY OF UNDERSTANDING”

——- Buddhist Saying

@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@

” ALL YOU GET FROM A TUNER IS AN OPINION”

——– Guitarist Leo Kottke

@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@

It’s more about being sensible …………

https://rockandice.com/videos/climbing/video-replica-border-wall-climbed-in-under-18-seconds/

Click on the above link to see how it can be done………

@@@@@@@@@@@@@@

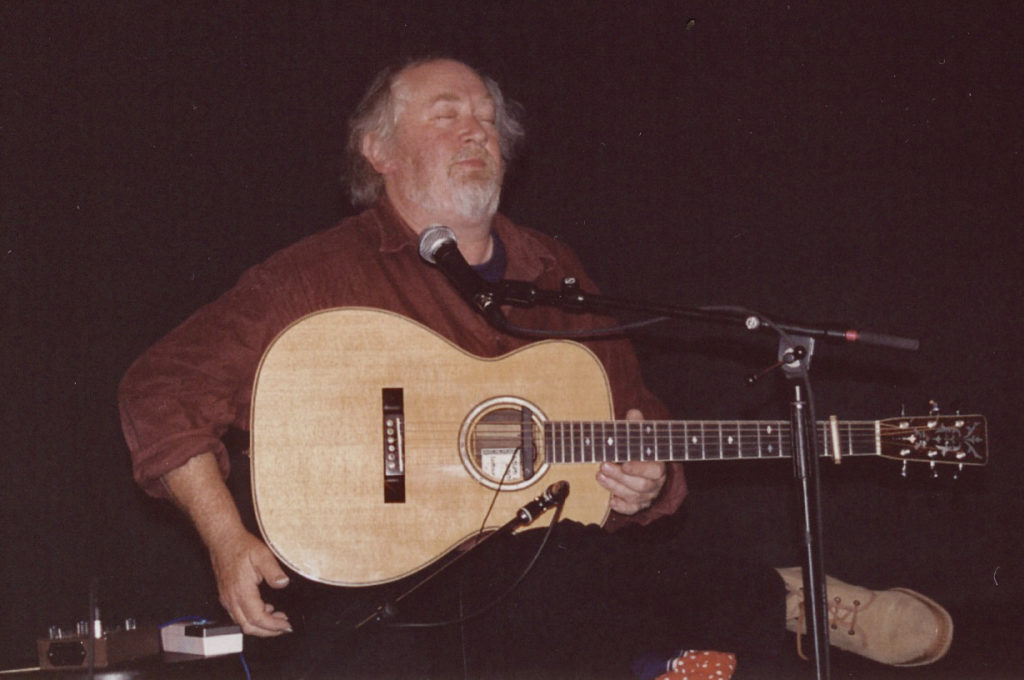

John Renbourn. Not exactly a household name in 2019 but back in the day (mid-1960s), his name was synonymous with the innovations in Acoustic Finger Picking guitar styles. That era was a hot bed of musical innovation for acoustic guitar players. In the UK and Ireland the “folk music revival” of that time fostered interest in the American acoustic finger picking styles of the Rev. Gary Davis, Doc Watson, Mississippi John Hurt, Elizabeth Cotten, Dave Van Ronk, Joseph Spence, Blind Lemon Jefferson, Merle Travis and many more “roots” musician. Guitarists of today probably do not realize the extent of the volatility of the acoustic guitar scene of that era. Memories of that scene have been somewhat over shadowed by the explosive growth of the “British Rock and Roll” phenomenon and the electric guitar scene that followed shortly after. At that time acoustic guitarists were very fortunate to be exposed to the increased availability of recorded material, a huge number of touring folk musician legends, and a steady improvement in the quality of acoustic instruments. The acceptance of the guitar into the traditional folk scene was not immediate. The guitar was then considered foreign to the unaccompanied vocal traditions that were prevalent in the British folk clubs. However, a number of acoustic guitarists adapted the imported styles and created blends of techniques and musical styles to create new, unique ways of playing “folk music”. Innovators of the day included Davey Graham (the inventor of DADGAD tuning), Nic Jones, Martin Carthy, Bert Jansch and of course John Renbourn. Most of the innovators have gone and the only one still playing at the peak of his powers is probably Martin Carthy. Nic Jones is till alive but still suffering the effects of a catastrophic car accident. On March 26, 2015 at the age of 70 years John Renbourn passed away.

I was very fortunate to be in Banff on Thursday, September 26, 2001. I was coming off a back packing trip to Mount Assiniboine when I spotted a poster for a concert by John Renbourn at the Banff Centre. I was fortunate enough to land a seat no more than six feet away from John. I had smuggled in my camera and I managed to snap some illegal photos right at the end of the show. That was just before I was nailed by the usher. It was a small price to pay for the opportunity. Apart from the music the thing that struck me most about this master musician was how old looked. He must have been only in his late 50’s but he looked more like eighty. He did have a reputation for living hard and it showed when he shuffled on stage, sat down and had to physically hoist his one leg across his knee to support his guitar. That didn’t seem to impair his technical ability or his musicianship. It was a memorable concert and one that has come flooding back after viewing this attached video.

I think the video speaks for itself. There are some interesting anecdotes as well as demonstrations of John’s playing. Clive Carroll is a name that is new to me but obviously one deserving of attention. His playing ranks right up there with other modern masters and I am looking forward to hearing more of his work.

Also here is a video of John performing one of his iconic master pieces – SWEET POTATO

After viewing the videos I went looking for the photos I took on that night to add to this blog. They are buried deep in the masses of photos I have taken over the years and I have not been able to find them. But all was not lost. I did a search on the internet and lo and behold I came up with a link to my original article written at the time. So here are the photos ……

All in all it has been a nice reminder that there is more to guitar playing than strumming three chords.

@@@@@@@@@@@@@@

https://mosaicscience.com/story/rwanda-cervical-cancer-hpv-vaccine-gardasil-cervarix/

The East African country’s campaign to end cervical cancer through the HPV vaccine has had to overcome cultural taboos and rumours about infertility – but it’s saving lives.

Girls began queuing at their local school with their friends, waiting for their names to be called. Many were apprehensive. After all, most of them had not had a vaccination since they were babies. It was 2013 and a new vaccine had arrived in Kanyirabanyana, a village in the Gakenke district of Rwanda. Reached by a reddened earth road, the village is surrounded by rolling hills and plantations growing crops from bananas to potatoes. Unlike the 10 vaccines already offered to young children as part of the country’s immunisation programme, this vaccine was different: it was being offered to older girls, age 11–12, in the final year of primary school.

Three years before, Rwanda had decided to make preventing cervical cancer a health priority. The government agreed a partnership with pharmaceutical company Merck to offer Rwandan girls the opportunity to be vaccinated against human papillomavirus (HPV), which causes cervical cancer.

This was the first time an African country had embarked on a national prevention programme for cervical cancer. Could Rwanda become the first country in Africa to eliminate it?

It was an ambitious goal. Cervical cancer is the most common cancer in Rwandan women, and there were considerable cultural barriers to the vaccination programme – HPV is a sexually transmitted infection and talking about sex is taboo in Rwanda. Added to this, rumours that the vaccine could cause infertility made some parents reluctant to allow their daughters to be vaccinated.

Rwanda’s economy and history also made it seem an improbable candidate for achieving high HPV vaccination coverage. After the 1994 genocide, it was ranked as one of the poorest countries in the world. High-income countries had only achieved moderate coverage of the HPV vaccine; if the United States and France couldn’t achieve high coverage, how could Rwanda?

Worldwide, cervical cancer is the fourth most common cancer in women. There were an estimated 570,000 new cases in 2018 – and over 310,000 deaths, the vast majority in low- and middle-income countries. Sub-Saharan Africa has lagged behind the rest of the world in introducing the HPV vaccine and routine screening, which means the cancer often isn’t identified and treated until it has reached an advanced stage.

Almost all cases of cervical cancer are caused by HPV. It is one of the commonest sexually transmitted infections globally, and most of us are infected with at least one type of genital HPV at some point in our lives – usually as teenagers or young adults. In most cases the virus is harmless and resolves spontaneously without causing any symptoms such as genital warts.

There are more than 100 strains of HPV, at least 14 of which can cause cervical cancer and a range of less common cancers, including of the penis, vagina and anus. Persistent infection with two strains of HPV, 16 and 18, is responsible for 70 per cent of cervical cancer cases.

The first vaccine against HPV became available in 2006. This was the culmination of decades of work, notably by scientists in Germany, who in 1983 discovered the link between HPV infection and cervical cancer.

Ian Frazer and Jian Zhou at the University of Queensland, Australia, then jointly developed the technology that enabled the HPV vaccine. Using recombinant DNA technology, they built the shell of the virus from scratch and made an ‘empty’ human papillomavirus in the lab.

“This was something nobody had achieved before,” Frazer says. They realised this empty, non-infectious HPV could be used as a vaccine to prevent HPV and cervical cancer.

The news that there was a new vaccine which could drastically reduce the number of women getting cervical cancer went around the world. But with the excitement about the new vaccine came the realization that not all girls would have the same opportunity to receive it. It was likely that at least a decade would pass between its introduction in high-income countries and in low-income countries.

Today there are three HPV vaccines – Gardasil and Gardasil 9, made by Merck, and Cervarix, made by GSK. All are highly effective at preventing infection with virus types 16 and 18. The newest – Gardasil 9 – was licensed in 2014 and protects against nine types of HPV, which between them cause around 90 per cent of cervical cancers.

More than 800,000 people died in the Rwandan genocide, and its widespread destruction left the country devastated. Coverage of most World Health Organization-recommended childhood vaccinations plummeted to below 25 per cent. But within 20 years, the number of babies in Rwanda receiving all recommended vaccinations, such as polio, measles and rubella, had increased to around 95 per cent. Rwandans’ life expectancy more than doubled between 1995 and 2011. The Rwandan government had demonstrated the determination and thoroughness of its approach to vaccinations. Could it now have the same success with HPV?

Before the HPV vaccine arrived in Kanyirabanyana, 63-year-old Michel Ntuyahaga, a community health worker, spent weeks canvassing his village, going to each of the 127 mud-brick houses to inform parents about the upcoming vaccination campaign.

Joined by a nurse, he explained to parents that if they had an adolescent daughter, they had an opportunity for her to be vaccinated against a deadly women’s disease – cervical cancer.

“I explained to parents that the cancer is a disease and that the one measure to prevent it is vaccination,” he says.

Ntuyahaga wasn’t the only person educating the community about the vaccination campaign.

Constantine Nyiransengiyera has been a primary school teacher in Kanyirabanyana for the past 13 years. In addition to teaching maths, science, French and English, she was – and continues to be – responsible for gathering all the 12-year-old girls at the local school to educate them about the HPV vaccine.

Silas Berinyuma, a leader in Kanyirabanyana’s Anglican church for the past 24 years, preached about the importance of the vaccine for weeks before it arrived in the village. The church used drama to depict scenes of cervical cancer’s devastating impact. This continues today.

The same awareness campaign was taking place around the country – Rwanda has a network of 45,000 community health workers, volunteers who are present in every village. Bugesera is a district in the Eastern Province, not far from the border with Burundi. Billboards line roads through the district, advertising soft drinks alongside public health messages. One says: “Talk to your children about sex, it may save their lives.”

Not far off the main road is Karambi, a village surrounded by banana plantations. Toddlers roll tyres down the red-earth roads, teenagers carry handfuls of firewood on their heads, and adults herd cows and goats.

In 2013, the then 12-year-old Ernestine Muhoza was vaccinated against HPV at her school. “The teachers called just girls for assembly and told us that there was a rise of a specific cancer among girls aged 12 and that it was time for us to get vaccinated,” she says.

When she went home to tell her parents about the vaccination, they’d already heard about it on the radio and via community health workers.

Muhoza’s parents readily agreed. But not every parent did. Some were sceptical. Why, they wondered, would their girls be getting vaccinated now, at this age? Why couldn’t all girls and women receive the vaccine? And rumour had it that the vaccine would make girls infertile.

Community health worker Odette Mukarumongi worked tirelessly in Karambi to counteract the rumours. “I told parents that a girl will go into constant menstruation – like endless bleeding – if she gets cervical cancer,” she says.

Mukarumongi says parents eventually “surrendered” and allowed their daughters to be vaccinated. Today, she says, parents rarely refuse, now that they can see the widespread acceptance of it in the community.

In Kanyirabanyana, Ntuyahaga worked similarly hard to convince parents that the vaccine wouldn’t stop their daughters from being able to conceive.

“Parents had heard that the vaccine made girls infertile. We struggled to explain to them it wasn’t true – that it was better to vaccinate their daughters against the cancer because if they got it they would become infertile,” he says.

Community health workers and nurses visited homes with posters of women’s reproductive organs to show parents the damage cervical cancer could do to their daughters.

Felix Sayinzoga, manager of the maternal, child and community health division at the Ministry of Health, says: “Rwandans are really afraid about cancer so it was easy [to roll the vaccine out]. It was also about the trust the community has in the government. That was really important – the community knows that we do not bring things that are not good for them.”

The current health minister, Diane Gashumba, agrees that trust in the government has been critical in supporting the vaccine’s uptake, but admits that the rumours surrounding it were difficult to quash.

“The rumours were not anticipated. But, of course, as the HPV vaccine was a new vaccine for a new target group there were many questions.” She adds that church and village leaders, community health workers and radio programmes played an integral role in dispelling myths about the vaccine.

Despite the vaccine’s potential to save lives – millions of them – HPV vaccination has been mired in controversy and hostility, and this has heightened in recent years.

The vaccine is recommended for girls, and in some countries for boys aged 12 to 13 too, because this is before sexual activity begins, bringing the risk of exposure to HPV. This has resulted in the vaccine being linked with promiscuity – a belief that vaccinating young girls against an STI sexualises them and encourages sexual activity. There is no evidence that boys or girls who receive the vaccine have sex earlier than those who do not have the vaccine. But this concern is one of the reasons that India – a country where more than 67,000 women die from cervical cancer every year – has refused to introduce HPV vaccine into its routine immunisation programme.

Leela Visaria, social researcher and honorary professor at the Gujarat Institute of Development Research in India, says: “The underlying reason why people don’t want it [the vaccine] is the fact it’s given to adolescent girls. They fear that girls will become promiscuous.”

Parents’ concerns about the HPV vaccine have been further fuelled by false claims about its safety. This misinformation has spread rapidly, worldwide, on social media. Japan’s take-up rate has plunged from more than 70 per cent to less than 1 per cent. Coverage has also dropped in parts of Europe, such as Denmark. In Ireland, conversely, a targeted social media campaign is reversing a sharp decline in the HPV vaccination rate.

Peter Hotez, a vaccine scientist and dean of the National School of Tropical Medicine at Baylor College of Medicine in Texas, agrees that there is a problem in the fears that the vaccine sexualises young girls. “The other problem is that the anti-vax movement has been making false assertions about it – claims that it leads to autoimmune diseases and paralysis.

“I think the movement is attempting to draw a line in the sand and say, ‘no more vaccines’ and when something like HPV comes along they are throwing everything they can at it. It’s having a devastating impact. I worry that we will start to export this garbage and it will impact vaccine uptake in Africa.”

“Initially, when the HPV vaccine was introduced in different countries, there were differences of opinion on whether to focus on HPV and how it’s transmitted, or to focus on the fact that HPV leads to cancer and this vaccine will prevent cancer,” says Mark Feinberg. He is the former chief public health and science officer at Merck who was involved with the Rwanda programme.

“Rwanda emphasised cancer prevention. It sought to communicate that the vaccine is here to protect young women from cervical cancer.”

Sayinzoga, from the Ministry of Health, agrees that policy makers made a conscious decision not to link the vaccine with sex. “For us, we didn’t associate the vaccine with sex. We rather focused on the side-effects of cervical cancer: that it can cause infertility. Sex wasn’t part of the campaign,” he says.

It’s a decision that is widely accepted by public health experts as the right one.

Ian Frazer, the immunologist who co-invented the first HPV vaccine, says: “The HPV vaccine has had a negative association. It has turned cervical cancer into an STI, which it is, of course, but we have to be careful. There is a right messaging for every country. Now we just talk about it as a vaccine to prevent cervical cancer. I think that’s the right strategy.”

In Karambi, Muhoza, who is now 17 years old, says: “You know, there are some things that cannot be talked about openly, especially when they relate to sex.”

When Rwanda and Merck signed their agreement, it meant that from 2011 the pharmaceutical company would supply the country with HPV vaccinations for three years at no cost.

As one of the world’s largest pharmaceutical companies, Merck wanted to demonstrate that it was feasible to introduce the vaccine in low-income countries in the hope that Gavi – a global health alliance to increase access to vaccination in these countries – would take note and get on board.

“Yes, Merck is a for-profit company, but our motivation was to maximize the impact of the vaccine. We wanted to find ways of enabling its innovations to be more broadly available,” says Feinberg, who is now president and CEO of the International AIDS Vaccine Initiative.

“You quickly recognise that you have a vaccine that can have such a major impact in preventing cervical cancer, and the greatest disease burden is concentrated in the world’s poorest communities. You cannot with any conscience not come forward and make the vaccine affordable and create a sustainable vaccination programme.

“The programme in Rwanda had two purposes: to get the vaccine to a population who could benefit, but also to demonstrate what was possible. Rwanda is an incredible country in its commitment to national health. If it wasn’t possible in Rwanda, we knew it wouldn’t be possible anywhere else.”

Rwanda’s decision to partner with Merck wasn’t without its critics. In a scathing letter to the Lancet, German public health researchers voiced “serious doubts” that the HPV programme was “in the best interest of the people”. A major issue, they contended, was that while the burden of cervical cancer in the region was substantial, there were far more pressing diseases to vaccinate against, such as tetanus and measles.

Rwanda’s then Minister of Health, Agnes Binagwaho, replied publicly in a letter co-signed by two US researchers. They said that Rwanda already had very high vaccination rates for tetanus and measles, and asked: “Are the 330,000 Rwandan girls who will be vaccinated against a highly prevalent, oncogenic virus for free during the first phase of this programme not regarded as ‘the people’?”

Drawing an analogy with earlier opposition to antiretroviral therapy in Africa, they said that such objections were “the latest backlash against progressive health policies by African countries. When the possibility of prevention exists, writing off women to die of cancer solely because of where they are born is a violation of human rights.”

Binagwaho, now vice-chancellor at the University of Global Health Equity in Rwanda, is still scathing about the critics of the decision to rollout the HPV vaccine. “The people who have created a backlash haven’t done their homework – they don’t know our country, they don’t know that our kids are well vaccinated with other vaccines available. [The HPV vaccine is] a great tool to prevent one of the most ravaging women’s cancers. It is less costly to prevent cervical cancer and all its suffering.”

Rwanda has proved to the world that it can achieve excellent HPV vaccination coverage. The Ministry of Health reports that 93 per cent of girls now receive the vaccine.

Almost all Rwandan girls attend school, and the systematic inclusion of local and religious leaders, community health workers and teachers in the vaccine delivery strategy has proved highly effective in spreading the message about the benefits of the vaccine and combating myths.

“I think some of the biggest reasons why Rwanda has been so successful is, first and foremost, the political will and national mobilisation, and secondly, that they decided to do a school-based programme,” says Claire Wagner, a student at Harvard Medical School who formerly worked as research assistant to Binagwaho.

The success in getting girls vaccinated has boosted confidence that the country is making rapid progress towards eliminating the disease. “We are working on our goal. We put our people first,” says health minister Gashumba.

Since 2006, over 80 countries have introduced the HPV vaccine into their routine immunization programmes. The majority are high-income, from Australia to the United Kingdom to Finland. These countries also have screening programmes for HPV and are moving from the pap smear test to a more advanced test, taken every five years, that detects high-risk HPV infections before cancer develops.

In Rwanda, before the HPV vaccine was introduced in 2011, there was no cervical cancer screening available in public health facilities – a few private clinics and NGOs offered it sporadically. Along with the vaccination programme, Rwanda also launched a national strategic plan for the prevention, control and management of cervical lesions and cancer. Women are meant to undergo visual inspection of cervix with acetic acid (VIA) at their local health centre or district hospital. Done by nurses and doctors, the screening is available to women with HIV aged 30 to 50, and other women aged 35 to 45. It’s unclear how effective and widespread this screening is.

“The problem with VIA is that one in five women will be positive but only 5 per cent need to be treated. That is an enormous cost to the healthcare system,” Frazer says. “If we want quick results we need to have some type of screening programme, but there’s a lot of debate about what that should look like in the developing world and how feasible it is.”

In Bugesera, community health worker Odette Mukarumongi says the closest health centre doesn’t do cervical cancer screening. Instead, she tells girls and women that if they experience any symptoms, like pelvic pain or constant menstruation, they should go to the health centre for a check-up.

Given that most cervical cancer cases occur in women in their 40s and 50s, if Rwanda is going to eliminate cervical cancer it will need a robust screening programme that reaches all women – women who have not benefited from the vaccine.

Countries across sub-Saharan Africa and Asia have struggled to implement cervical screening programmes. Given geographical challenges, lack of funding, and competing health issues such as HIV and malaria, cervical cancer hasn’t been a priority for most policy makers. While it accounts for less than 1 per cent of all cancers in women in high-income countries, in low- and middle-income countries it’s almost 12 per cent. This is why the HPV vaccine is so critical: for girls and women in these countries it is their best – and often only – line of defence against the disease.

Another factor in the success of Rwanda’s campaign to end cervical cancer will be its ability to sustain the HPV vaccination programme. In 2014, Merck’s donation of Gardasil ended. As Feinberg had hoped, the Gavi alliance announced it would support Rwanda’s HPV programme through a co-financing model. Rwanda pays 20 cents per dose of the vaccine, and Gavi covers the remainder of the $4.50 cost. As the country’s economy continues to grow, its co-financing obligations will rise until it reaches a threshold after which Gavi support will phase out over a five-year period. Eventually, Rwanda will fully finance its HPV vaccine.

Will the country be able to afford this?

Sayinzoga from the Ministry of Health admits he’s concerned about the country’s ability to pay for the vaccine in future. “The HPV vaccine is very expensive. What we are doing annually is looking at how we can plan for the next three years. We were in need and we accepted Merck’s help. We need to invest in the life of our people,” he says.

Gashumba says the Ministry is exploring options to make the vaccination programme sustainable, such as including the vaccine in health insurance.

Whatever the challenges in the future, Rwanda has today achieved remarkably high coverage of the HPV vaccine for girls – an extraordinary public health achievement that should inspire countries around the world.

As Rwanda gears up for a new round of vaccinations later this year, the immunologist responsible for the vaccine that has saved so many women’s lives believes the world cannot be complacent. “You can’t be happy until everyone has been vaccinated,” Frazer says.

@@@@@@@@@@@@@@

“Human papilloma virus (HPV) vaccines are vaccines that prevent infection by certain types of human papillomavirus.[1] Available vaccines protect against either two, four, or nine types of HPV.[1][2] All vaccines protect against at least HPV type 16 and 18 that cause the greatest risk of cervical cancer.[1] It is estimated that they may prevent 70% of cervical cancer, 80% of anal cancer, 60% of vaginal cancer, 40% of vulvar cancer, and possibly some mouth cancer.[3][4][5] They additionally prevent some genital warts with the vaccines against 4 and 9 HPV types providing greater protection.[1]

The World Health Organization (WHO) recommends HPV vaccines as part of routine vaccinations in all countries, along with other prevention measures.[1] The vaccines require two or three doses depending on a person’s age and immune status.[1] Vaccinating girls around the ages of nine to thirteen is typically recommended.[1] The vaccines provide protection for at least 5 to 10 years.[1] Cervical cancer screening is still required following vaccination.[1] Vaccinating a large portion of the population may also benefit the unvaccinated.[6] In those already infected the vaccines are not effective.[1]

HPV vaccines are very safe.[1] Pain at the site of injection occurs in about 80% of people.[1] Redness and swelling at the site and fever may also occur.[1] No link to Guillain–Barré syndrome has been found.[1]

The first HPV vaccine became available in 2006.[1][7] As of 2017, 71 countries include it in their routine vaccinations, at least for girls.[1] They are on the World Health Organization’s List of Essential Medicines, the most effective and safe medicines needed in a health system.[8] The wholesale cost in the developing world is about US$47 a dose as of 2014.[9] In the United States it costs more than US$200.[10] Vaccination may be cost effective in the developing world.[11] —– Wikipedia

“Research studies have shown early signs of the vaccine’s success including: a 77% reduction in HPV types responsible for almost 75% of cervical cancer. almost 50% reduction in the incidence of high-grade cervical abnormalities in Victorian girls under 18 years of age.”

“How effective is the HPV vaccine? The HPV vaccine provides almost 100% protection from nine HPV types 6, 11, 16, 18, 31, 33, 45, 52 and 58), if all doses are received at the correct intervals, and if it is given before you have an infection with these types.” —– Wikipedia

@@@@@@@@@@@@@@

I think the video speaks for itself:

@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@

If there is ever a right person at the right place at the right time then Jacinda Kate Laurell Ardern is it. She is the current Prime Minster of New Zealand, one of the youngest leaders on the world stage with a political style and personal popularity that must be the envy of politicians everywhere. Oh, by the way she gave birth to a baby while in office. Here is a clip of Jacinda in action at the UN during the same session that was also addressed by Donald Trump. What a contrast between her lucid, positive logical speech and Donald Trump’s boorish presentation filled with negativity. The contrast of a passionate young woman versus the tired rhetoric of a fat old white man is so glaring that it is easy to believe that the USA Empire is in decline.

New Zealand is incredibly fortune to have Jacinda at the helm during the Christchurch Massacre. Her empathy with the victims, her swift condemnation of racism and almost immediate implementation of strict Gun Control can only be praised and admired.

Politically this is what she is about (Wikipedia):

Ardern has described herself as a social democrat, a progressive, a republican and a feminist citing Helen Clark as a political hero, and has called capitalism a “blatant failure” due to the extent of homelessness in New Zealand. She advocates a lower rate of immigration, suggesting a drop of around 20,000–30,000. Calling it an “infrastructure issue”, she argues, “there hasn’t been enough planning about population growth, we haven’t necessarily targeted our skill shortages properly”. However, she wants to increase the intake of refugees.

Ardern believes the retention or abolition of Maori electorates should be decided by Māori, stating, “[Māori] have not raised the need for those seats to go, so why would we ask the question?” She supports compulsory teaching of the Maori language in schools.

On social issues, Ardern voted in favor of same-sex marriage and believes abortion should be removed from the Crimes Act. She is opposed to criminalizing people who use cannabis and has pledged to hold a referendum on whether or not to legalize cannabis in her first term as prime minister. In 2018, she became the first prime minister of New Zealand to march in a gay pride parade

Referring to New Zealand’s nuclear-free policy, she described taking action on climate change as “my generation’s nuclear-free moment”.

Ardern has voiced support for a two state solution to resolve the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. She has condemned the deaths of Palestinians during protests at the Gaza border.

@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@

The accused perpetrator of this horrendous act in Christchurch, New Zealand (Friday, March 15, 2019) is a 28 year old Australian. Why did it take place in New Zealand and not Australia? This is conjecture on my part, but I think the answer to the question may be fairly simple – the gun laws in Australia are more stringent than in New Zealand. He may have had easier access to his weapons of choice in a country that has an entrenched gun culture. For many years New Zealand has had an eradication policy for all non-indigenous animals that have proven to be detrimental to the ecology of the islands. These include pigs, possums, deer and other species. The result is that recreational hunting is a way of life for a significant number in the community. There are huge recreational and commercial interests at stake in any discussion of gun control and these interests resist any restriction on the ownership and use of guns. To get some idea of the commercial interest at stake, in the early 1970s there was a newspaper article on the commercial hunting of deer in the South Island. Commercial venison providers would drop freezer units and staff into select locations to dress slaughtered animals for export as frozen venison. To achieve maximum use of resources hunters would go into remote valleys in military style gunship helicopters and with automatic weapons shoot animals from the air. The article went on to state that as many as three thousand animals a week were being taken out of some of these valleys. This was (is) big business. So with the potential push back by recreational hunters and commercial operations it is easy to see why there has been some difficulty in reforming gun laws.

Prior to 1996 Australia did have, and possibly still has a significant gun culture, who oppose gun law reform. But that all changed in 1996. Around April 28-29 of that year a gunman armed with a semi-automatic rifle went on a rampage in Port Arthur, Tasmania, killing 35 and wounding 23 people. It was the deadliest mass shooting in Australian history. Over night it precipitated fundamental changes in the gun control laws of that country. Within 12 days of the incident John Howard, the Prime Minister of Australia, co-ordinated an agreement that created the National Firearms Agreement (NFA), also sometimes called the National Agreement on Firearms, the National Firearms Agreement and Buyback Program, or the Nationwide Agreement on Firearms. The laws to give effect to the Agreement were passed by Australian State governments only 12 days after the Port Arthur massacre. Despite lobbying against the NFA by The Christian Coalition supported by the US National Rifle Association the changes to the gun laws went ahead with broad support from all across the political spectrum and the community at large. The NFA placed tight control on semi-automatic and fully automatic weapons, but permitted their use by licensed individuals who required them for a purpose other than ‘personal protection’. The act included a gun buy-back provision. Some 643,000 firearms were handed in at a cost of $350 million. Numerous studies of the impact of the NFA have been either inconclusive or contradictory and yet, one study found that there were no mass shootings in Australia from 1997 through 2006.

Gun laws in New Zealand focus mainly on vetting firearm owners, rather than registering firearms or banning certain types of firearms. Over recent years there have been efforts to reform gun laws but these do not seem to have brought about significant change. The day after more than 40 (now updated to 50) were killed in mass shootings at two mosques in the worst terror attack in the nation’s history, The Prime Minister of New Zealand, Jacinda Arden in a press conference said “I can tell you one thing right now: Our gun laws will change”. She went onto to say “the suspected primary shooter used five guns, including semiautomatic weapons and shotguns, adding that he obtained a gun license in November 2017 and acquired the guns legally thereafter. That will give you an indication of why we need to change our gun laws.”

So, as Yogi Berra once said is this “Déjà Vu all over again”? In terms of political response one can hope so.

@@@@@@@@@@@@@@

Post Christchurch Massacre – The Power of the Haka

@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@

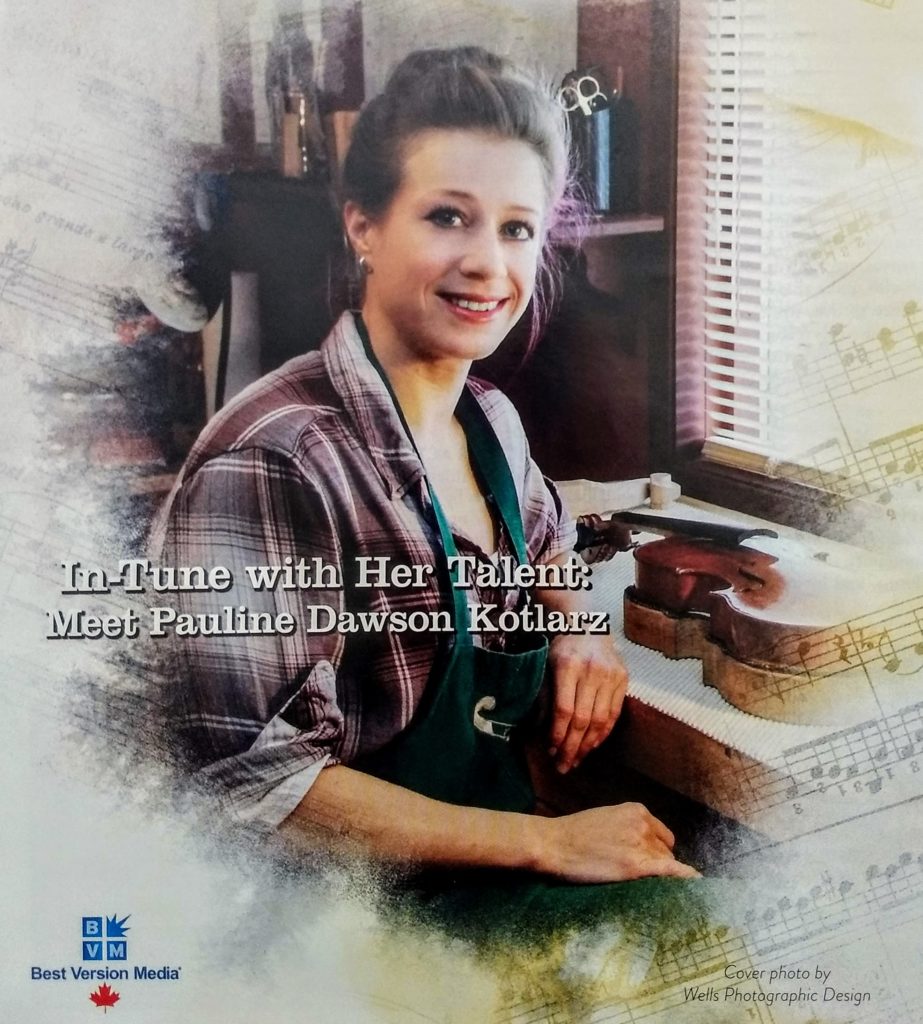

“My name is Pauline Kotlarz and I am a Luthier. I was trained through the Violin Making School of America in Salt Lake City (2011-2014). Since then I have worked in a full repair and restoration shop in Wisconsin for the past three years while making new violins on the side. I have experience doing quality work on making, maintaining and repairing violins, violas and cellos. I’m originally from Cranbrook, and although it’s been a long and circuitous route to come home, I’m happy to be back and to offer my skills and services to any musicians in the area. Some common repair and maintenance services I offer include cutting new posts/bridges, fingerboard dressings, nut adjustments, peg fittings, clean&polish, new strings, varnish touch-ups, crack and seam gluing. There is no one-size fits all; everything is custom work according to the instrument and player. Verbal repair estimates are free and best done in person. I also sell my handmade violins and commercial violins with professional set-ups on a customer demand-basis. I am a small shop with limited inventory but will work with customers to procure stock items they desire at reasonable prices. My shop is based out of my home and by appointment only. I unfortunately do not work on fretted instruments (ie guitars, mandolins, etc) and I don’t do bow re-hairs; however, I’m happy to refer customers to luthiers experienced in those skills. I am passionate about what I do, and if I can be the catalyst for someone else’s improvement and enjoyment of playing music through application of my luthiery skills then I will have done my job.”

For consults and inquiries Pauline can be contacted by phone at (250)-464-0918 or by emailing her at kotlarzviolins@gmail.com

@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@

“The Medium is the message” …….. This catch phrase is from the writings of Marshall McLuhan. He coined it way back in the 1960s. I never really got “it” then and I am not even sure I get it now. However, the following is a reprint of an article that I came across recently and it goes a long way to explain the recent resurgence of interest in Vinyl Recordings.

Ask a record-collecting audiophile why vinyl is back and you may hear a common refrain: “Of course vinyl’s back! It’s a more accurate reproduction of the original! It just sounds better than digital!”

To this I reply, “Does it really, though? Or is it just EQ’d better? And since when did we start caring so much about the perfect fidelity of our recordings? I grew up—as did many of you—listening to cassette tapes on a boom box. They sounded horrible, and we loved them.”

I think the real reason for vinyl’s return goes much deeper than questions of sound quality. As media analyst Marshall McLuhan famously wrote, “The medium is the message.” In other words, “the form of a medium embeds itself in any message it would transmit or convey, creating a symbiotic relationship by which the medium influences how the message is perceived.” Nowhere does this hold truer than in the world of recorded sound.

The entire experience of vinyl helps to create its appeal. Vinyl appeals to multiple senses—sight, sound, and touch—versus digital/streaming services, which appeal to just one sense (while offering the delight of instant gratification). Records are a tactile and a visual and an auditory experience. You feel a record. You hold it in your hands. It’s not just about the size of the cover art or the inclusion of accompanying booklets (not to mention the unique beauty of picture disks and colored vinyl). A record, by virtue of its size and weight, has gravitas, has heft, and the size communicates that it matters.

Records, in all their fragility and physicality, pay proper respect to the music, proper respect to the past. They must be handled carefully, for the past deserves our preservation. They are easily scratched, and their quality is diminished as a result of those scratches. They are subject to the elements—left in the sun, they warp. Like living things, they are ephemeral.

While the process of launching Spotify and searching for a track (Any track! You have 30 million choices!) is clearly the most efficient means of listening to music, sometimes efficiency isn’t what the experience is about. Record albums are analog, the closest thing we have to the sound waves. These waves are coaxed out of a flattened, spinning disk of vinyl by a diamond. The diamond is literally taking a ride on the record. The bumps in the grooves push the diamond up and down. Everything about the process has a tactile physicality to it that differs in feel from digital services.

Steven Beeber, the vinyl aficionado and author of The Heebie-Jeebies at GBGB’s: A Secret History of Jewish Punk summed up the appeal of records this way: “As with so many things, the Luddites were right. The old ways were better. Vinyl has a richness and depth that digital media lacks, a warmth, if you will. And hell, even if it didn’t, it sure looks cool spinning on the table, and you’ve got to treat it with kindness to make it play right, so it’s more human too. As in our love lives, if you want to feel the warmth, you’ve got to show you care.”

Beeber’s last point hits at the crux of vinyl. The cumbersome process of putting on a record is akin to a ritual, an experience that mirrors the care that artists took in creating the work. First you have to find the record—a treasure hunt which might take five or 10 minutes depending on the size and organization of your collection. When you find the record, you pull it out. You remove the album from its cover. (Or, if you’re a real stickler, you remove the album from the cover, still inside the inner sleeve. Because at some point you rotated the inner sleeve 90 degrees to prevent the album from accidentally slipping out. So you pull out the album in its sleeve.) Then you place the record gently on the turntable spindle: the hole so accurately punched that you need to push the album firmly down to get it to sit right.

The album and the turntable needle are both objects that demand your respect. The record must be freed of dust, so you get out your Discwasher D4+ System. You remove the wood-handled brush from the cardboard box. You remove the small red bottle of Hi-Technology Record Cleaning Fluid, along with the tiny red-handled needle brush, both of which are cleverly nestled inside the wooden handle. You gently sweep the needle with the brush, which produces a satisfying whooshing from the speakers.

Then you apply 3-6 drops of D4 fluid to the cloth-covered face of the wood-handled brush and rub it in with the base of the bottle. Then you place the wood-handled brush on the record, careful to orient the nap in the right direction. Then you lick a finger of the other hand, place it in the center of the record, and gently rotate the platter beneath the brush. When these tasks are complete, then—and only then—do you set the platter in motion and lower the needle—slowly, ever so slowly—onto the spinning vinyl disk.

And the music begins to play.

The record experience suggests a few possible lessons for user-interface designers:

1) Designing for multiple senses can be more powerful than designing for just one. This is why mobile apps that incorporate sound (button clicks, etc.) and tactile sensations (haptic feedback) in addition to visual cues create greater user delight than those that are purely visual.

2) Always design in a manner appropriate for the medium.

3) Always consider the user’s state of mind. Consider every aspect of their psychology and how it might relate to the experience at hand. For instance, a person might find one experience preferable to another, because it reminds them of their childhood, or because that’s how they’ve always done it. (Case in point: my mother always preferred grinding her coffee beans with a hand-cranked grinder, because that’s how she always did it—not because she thought that the beans tasted better.) There might also be a touch of rebellion in the act of rejecting today’s technology for a simpler tool that worked just fine, thank you very much.

Not everything in life is about ease and speed. Believe it or not, sometimes people want to take longer, particularly if an experience evokes a past memory, satisfies a deep-rooted need, or fills a behavioral gap. Make anything too easy and its perceived value declines.

Some people, some of the time want the process of listening to music to demand respect from them, to offer an embodied ritual that removes us for a time from the daily humdrum of our digital existence. Speed has its place, but time spent can signal value and create a pleasant weight of meaning. There’s a reason our religious services aren’t five minutes long, and we shouldn’t lose sight of that as digital technologies continue to dominate our lives.

@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@