The three DVD set Sound Breaking was released a couple of years back. It was marketed as “The art and evolution of music recording is one of the 20th century’s untold stories” and the set was meant to set the story straight. It achieved some of that but the story was heavily slanted towards pop music and pop culture. For me the first disc, with its explorations of the Beatles, is the most interesting, while the remainder of the set about, rap, hip hop, sampling, etc, is of no interest to me. Admittedly the object of the exercise was to explore the history of pop music but in doing so it omitted at least one of the recording industry’s most notable personalities – Rudy van Gelder. For those who are unaware of the name or his significance Rudy was responsible for recording a very significant slice of the jazz spectrum in the 1950s, 60s, and right up into the new century. He is the creator of what became known as the Blue Note Sound.

This is his Wikipedia entry:

Rudolph Van Gelder (November 2, 1924 – August 25, 2016) was an American recording engineer specialized in jazz. Regarded as the most important recording engineer of jazz by some observers, Van Gelder recorded several thousand jazz sessions, including many recognized as classics, in a career which spanned more than half a century. Van Gelder recorded many of the great names in the genre, including John Coltrane, Miles Davis, Thelonius Monk, Sonny Rollins, Art Blakey, Joe Henderson, Freddie Hubbard, Wayne Shorter, Horace Silver, Grant Green as well as many others. He worked with many record companies but was most closely associated with Blue Note Records. The New York Times wrote his work included “acknowledged classics like [John] Coltrane’s A Love Supreme, [Miles] Davis’s Walkin’, Herbie Hancock’s Maiden Voyage, Sonny Rollins’s Saxophone Colossus, and Horace Silver’s Song for My Father .

In this day and age of the resurgence of vinyl recordings I think this is one of his most significant comments:

“The biggest distorter is the LP itself. I’ve made thousands of LP masters. I used to make 17 a day, with two lathes going simultaneously, and I’m glad to see the LP go. As far as I’m concerned, good riddance. It was a constant battle to try to make that music sound the way it should. It was never any good. And if people don’t like what they hear in digital, they should blame the engineer who did it. Blame the mastering house. Blame the mixing engineer. That’s why some digital recordings sound terrible, and I’m not denying that they do, but don’t blame the medium.” (Audio Magazine 1995)

His fame still lives on and the following is a reprint of an article from the now defunct Audio Magazine. It has recently been resurrected resurfaced by the editorial staff at JazzProfiles. Steve Cerra introduces the article:

“I never thought much about the quality of the sound on the Blue Note LPs that I purchased in the 1950s and 60s. I didn’t need to. Blue Note’s sound quality was something that one could take for granted because the now, legendary Rudy van Gelder was the commanding force behind it and, as you’ll come to understand after reading the following interview, he obviously gave it a great deal of thought.

The sound on Blue Note’s albums had a “presence” that wrapped the listener in an audio environment which was dynamic and vibrant. The sound came forward; it reached out; it enveloped. Rudy made the sound seem as though it was emanating from musicians who were performing it in one’s living room. In a way, this is more than an analogy because Rudy’s initial recording studio was the living room in his parents’ home in Hackensack, NJ before he built his own studio in near-by Englewoods Cliffs, NJ.

Rudy doesn’t talk much about himself or his views on the subject of sound engineering. Fortunately, James Rozzi was able to interview him at length and publish Rudy’s responses to his questions in the November 1995 edition of the now defunct Audio Magazine.

The editorial staff at JazzProfiles thought this rare glimpse of Rudy van Gelder discussing himself and his technical approach to sound recording would make an interesting feature for its readers. It is hard to imagine let alone conceive of what The World of Jazz would have been like if Rudy Van Gelder hadn’t been around.

James Rozzi original article (copyright protected)

“Dr. Rudy Van Gelder’s formal education was in optometry, but his heart and the majority of his professional years have been devoted full-time to the recording industry. Ask any Jazz buff about Rudy, and they’ll name him as the recording engineer responsible for all those classic Blue Note and Prestige Records, among almost countless others.

This interview, one of the very few that Rudy has granted in his 40 plus years in the business, was conducted in his Englewood Cliffs, NJ studio, a gorgeous facility just across the George Washington Bridge from Manhattan. I thank him for sharing his history and his views.

It’s a given in the Jazz world that you have set the standards for Jazz recordings for the past 40 years. In an ever-changing industry, how do you continue to maintain consistent quality in your recordings?

I prefer to do my own masters, my own editing. By ‘my own,’ I mean, I want it to be done here. It’s not that I influence what it is. It’s just that I need to be involved in the whole process – up to and including the finished product – in order to give my clients what they expect of me, which is the reason why they are coming here. They agree upon that before we can do anything. This is really the only major stipulation I have, that I do the process. It’s not because it is expensive, because the expense is minimal. I purposely keep it that way because I don’t want the money to be a part of their decision. The point is that I’d like to have at least some measure of control over the finished sound before it’s sent for replication to the plant.

This is contrary to the way most studios work.

The business, at least from my point of view, has really become fragmented – more like the movie industry. There are engineers who do Jazz recording who don’t own the studio and don’t have anything to do with the maintenance, ownership or operation of the studio. They just go to a studio as a freelance engineer and use the facility for their own clients. Obviously, this is not the situation here. I own the studio, I run the studio and I maintain it. It’s my responsibility, I’m here everyday, not somebody else. It reflects me.

Being involved in the complete digital post-production is highly unusual for any studio. Would you please explain it?

Once we have gotten to the point of recording and mixing the two-track tape that has all of the tunes the client wants for the CD, the next step is to get together with the producer or the musician, whoever is in charge of the project – and sequence it. We have to put the tunes in the order that they will appear in on the CD, get all the timings in between the songs precise, and takes all the noises out. As for the medium for that, the most common medium is DAT [digital audio tape]. Now most people – including musicians and producers, except for those who work here – believe that this is a master tape. That format was not designed to be and is incapable of being a master. There are other elements required for CD replication that cannot be incorporated into a DAT. There is just no room on a DAT for the information which tells your CD player to go to track one when you put a CD in and press “play.” The information that makes this possible has to be incorporated on the CD. The DAT must be transferred to another medium that incorporates this information. This studio uses a CD-R. Prior to the CD-R, 1630 was the de facto standard. I consider that now obsolete. Most recording studios do not get involved in this process.

If most recording studios don’t get involved in digital post-production, then how is it commonly done?

The very fact that most recording studios don’t care to do it has created the existence of what are called mastering houses. They don’t have studios. They don’t even have a microphone. They just put the numbers on there and then transfer from one medium to another.

Why are you so concerned with accomplishing this process yourself? Isn’t the equipment expensive?

Yes, it’s very expensive, very difficult to acquire and maintain. The problem is that there can be processing at this stage, quite extensive processing.

Intentionally changing the sound from that of the DAT?

Intentionally changing the sound! Changing the loudness to softness, the highs to lows. Yes, it’s a very elaborate procedure; it is a part of the recording process that most people don’t even know exists.

Who is responsible for making the decision to alter the sound at this late a stage in the recording process?

Whoever is following the course of the project, usually whoever is paying for it or their representative. I’m now defining why I insist on doing everything myself. And you can extend this into the reissue process too. Reissuing is nothing but post-production. The people who were originally involved in the recording are no longer there, or they no longer own it. These mastering decisions on reissues are being made by someone else, someone affiliated with the company who now owns the material.

What are your feelings on issuing alternate takes?

Now, to me that’s just a sad event which has befallen the record industry. The rejected outtakes have been renamed “alternate takes” for marketing reasons. It’s a disservice to the artist. It’s a disservice to the music. It’s also rampant throughout the land, and I’m just telling you how I feel about it. I would recommend to all musicians: Don’t let the outtakes get out of your hands. Of course, that may be easier said than done.

You must be disappointed by much of what has been released as alternate takes.

Yes, when I hear some of this stuff, I’m reminded of all the problems I had, particularly on these outtakes. It’s like reliving all of the difficulties of my life again. So I don’t take a lot of pleasure in that because I know I can do a lot better now, and all that does is reinforce my uneasiness. Of course, when it was a recording problem, the music was usually still so good that it was worth it to me. And the fact that it’s still being heard— in many cases being heard better than ever before—is an incredible experience. And it’s clean, with no noise. I don’t like to complain too much.

I feel that way very often myself, the way you described, being able to hear the music better than ever. I’m not a person who locks into the sound as closely as I do the music. The music is all-important to me, but sometimes I become distracted by how bad the sound is. It seems that a big problem in translating those old recordings onto CD is the sound of the bass. It becomes very boomy.

Well, you can’t blame that entirely on the people who are doing the mastering. That particular quality is inherent in the recording techniques of the time—the way bass players played, the way they sounded, the way their instruments sounded. They don’t sound like that now. The music has changed the way the artists play. Now everything has got to be loud. A loud .drummer today is a lot louder than a loud drummer of 30 or even 20 years ago. It’s all relative. But as far as that certain quality you’re talking about, some of it is very good, by the way. There were some excellent bass recordings made at that time because the bass player and I got together on what we were trying to do.

Considering the reverence given to the historical Blue Note recordings and the fact that they were accomplished direct to two-track, do you get many requests nowadays to record direct to two-track?

Usually they say, “I want to go direct to two-track like the old days.” And I say, “Sure, I’ll do that.” I can still do it, or we can record to the 24-track digital machine. As far as the musicians are concerned, regarding their performance out in the studio, that’s transparent to them. There’s no difference in the setup. I sort of think two-track while I’m recording and actually run a two-track recording of the session, which very often serves as the finished mix. But this is the real world now. The musicians will listen to the playback, and the bass player will say, “Gee, I played two bad notes going into the bridge of the out-melody. Can you fix that, Rudy?” Now, it used to be that when a client asked for a two-track session, I would never run a multi-track backup. They didn’t want to get involved in it, for money reasons. They didn’t want to spend the money for the tape or didn’t want to have to mix it after the session. I went along with that for a long time. But the bass player would still come in, hoping to fix wrong notes, and I’d sit there like a fool and say, ‘Well, I can’t do anything about it. The producer didn’t want to spend the money for multi-tracking.’ So I decided I wasn’t going to do that anymore. I think of it as a two-track date— we’re talking about a small acoustic jazz band now, not any kind of heavy production thing—and I run a multi-track backup. Then when the bass player asks to fix a couple of notes, I look at the producer or whoever is paying for the session, and that becomes his decision, not mine. He now has to answer the bass player.

So the final product may consist of both multi-track and two-track recordings?

That happens. Right. And my life is a lot happier. And the producers have come around a little bit too.

How did you first become affiliated with Alfred Lion of Blue Note Records?

There was a saxophone player and arranger by the name of Gil Melle. He had a little band and a concept of writing, and I recorded him. This was before I met Alfred. I recorded it in my Hackensack studio in my parents’ home. So somehow—and I was not a party to it—he sold that to Alfred to be released on Blue Note. And Alfred wanted to make another one. So he took that recording to the place he was going. It happened to be in New York at the WOR recording studios. He played it for the engineer, who Alfred had been using up until that time, and the engineer said, “I can’t get that sound. I can’t record that here. You’d better go to whoever did it.” Remember, I wasn’t there; this is how it was related to me. And that’s what brought Alfred to me. He came to me, and he was there forever.

Those Blue Note records, they’re just so beautiful…. Masterpieces.

Did Alfred and you work at producing those jazz masterpieces? Did he have you splice solos?

Yes, he did. He was tough to work for compared to anyone else. He knew what he wanted. He knew what that album should sound like before he even came into the studio. He made it tough for me. It was definitely headache time and never easy. On the other hand, I knew it was important, and he had a quality that gave me confidence in him. The whole burden of creating for him—what he had in mind—that was mine. And he knew how to extract the maximum effort from the musicians and from me too. He was a master at that. I think one of the reasons our relationship lasted so long was because he listened to what other people were doing parallel to our product. I don’t believe he ever heard anything that was better than what we were doing. I have no doubt that if he had heard someone doing it better than what I was doing, he would have gone there. But he never did, and that made it possible for me to build this studio. I knew he was always there.

Once you developed that sound, you knew exactly what to do initially. When the musicians walked in, you knew right where everything should be regarding microphone placement and all of that. And you went from there. From that point, it was just minor alterations according to that session.

That’s very well put, and do you know why that was? Because Alfred used to come here often. He used to bring the same people out in various combinations. They all knew what I was like. Everybody would come in and know exactly where their stand was, where they would play. It was home. There were no strangers. They knew the results of what they were going to do. There was never any question about it, so they could focus on the music.

Then when Bob Weinstock of Prestige Records started with you, there was that whole crowd of musicians, sometime crossing over personnel.

Well, Weinstock would very often follow Alfred around, but with a different kind of project in mind. And you know, when I experimented, I would experiment on Bob Weinstock’s projects. Bob didn’t think much of sound; he still doesn’t. He doesn’t care. So if I got a new microphone and I wanted to try it on a saxophone player, I would never try it on Alfred’s date. Weinstock didn’t give a damn, and if it worked out, great. Alfred would benefit from that.

I’ve always thought of the Prestige dates as a more accurate indication of what was happening in the clubs. Although I know that after a Blue Note session wound down, the musicians could go out into the clubs and play original tunes, with Prestige it was mostly standards. That’s what they went out and jammed on. And that deserves documentation as well.

Absolutely. I agree with that, and I’ve said so, though not as well as you did. I wouldn’t want the world to be without them. There are people who say that the difference between Blue Note and Prestige is rehearsal. That’s just glib. That’s bullshit. That’s not even a fair way to put it. It resulted in a lot of my favorite recordings. You know, those Miles [Davis] Prestige things … they can’t hurt those things. It’s really one of the most gratifying things I’ve done, the fact that people can hear those. It’s really good.

When you were in the control booth listening to the sessions, were you ever aware that those sides would end up as classics?

Well, you can’t see into the future. I had no way of knowing that. But I knew every session was important, particularly the Blue Note stuff. The Blue Note sessions seemed more important at the time because the procedure was more demanding. But in retrospect, the Prestige recordings of Miles Davis, the Red Garland with Philly Joe Jones, the Jackie McLean and Art Taylor, the early Coltrane—sessions like that—turned out to be equally if not more important. I always felt the activity we were engaged in was more significant than the politics of the time, to the extent that everything else that was happening was unimportant. And I still feel that way. I treat every session … every session is important to me.

Have you done any classical or pop?

There was a long period of time parallel to those years when I was working for Vox, a classical company. I would get tapes from all over Europe and master those tapes for release in this country. I did that for 10 years or more. So I had three things going: Blue Note, Prestige, and Vox. Each of them was very active. And I did some classical recordings: Classical artists, solo piano recordings, a couple of quartets.

How about pop?

A lot of that popular stuff came with Creed Taylor later in the ’70s. He was oriented more toward trying to commercialize jazz music. You’re familiar with his CTI label? That’s another world altogether. That’s when we started to be conscious of the charts. I love the sound of strings, particularly the way Creed Taylor handled them with Don Sebesky. And I love an exciting brass sound too. Creed is a genius as far as combining these things that we’re talking about. I’m not at all isolated in the world of a five-piece be-bop band. As a matter of fact, sonically, this other thing is more rewarding.

What are your feelings on digital versus analog?

The linear storage of digital information is idealized. It can be perfect. It can never be perfect in analog because you cannot reproduce the varying voltages through the different translations from one medium to another. You go from sound to a microphone to a stylus cutting a groove. Then you have to play that back from another stylus wiggling in a groove, and then translate it back to voltage. The biggest distorter is the LP itself. I’ve made thousands of LP masters. I used to make 17 a day, with two lathes going simultaneously, and I’m glad to see the LP go. As far as I’m concerned, good riddance. It was a constant battle to try to make that music sound the way it should. It was never any good. And if people don’t like what they hear in digital, they should blame the engineer who did it. Blame the mastering house. Blame the mixing engineer. That’s why some digital recordings sound terrible, and I’m not denying that they do, but don’t blame the medium.

A lot of people argue that digital is a colder, sterile sound. Where do you think that comes from?

Where does it come from? The engineers. You’ve noticed they’ve attributed the sound to the medium. They say digital is cold, so they’ve given it an attribute, but linear digital has no attributes. It’s just a medium for storage. It’s what you do with it. A lot of this has to do with the writing in consumer magazines. They’ve got to talk about something. What should be discussed is the way CDs are being marketed as 20-bit CDs, but there is no such thing as a 20-bit CD. Every CD sold to the public is a 16-bit CD. You can record 20-bit and it is better than 16-bit, but it has to be reduced to 16-bit before you can get it onto the CD. History is repeating itself. It reminds me of when they marketed mono recordings as “re-mastered in stereo.” All they did was put the highs on one side, put the lows on the other, and add a lot of reverb to make it believable. Then they’d sell it as a stereo record.

Do you feel today’s jazz musicians stack up to the players of the 1950s and ’60s, Blue Note’s heyday?

Well, there are a lot of great kids around. You know, technically they’re great. I feel they’re suffering from a disadvantage of not being able to play in the kind of environment that existed then. You don’t want me to make a broad statement saying, “Gee whiz, it was better 20 years ago than it is now.” First of all, I don’t believe that. I don’t even think of it that way.

Do you see yourself as a technician and an artist?

Absolutely. When you mention the technical end, the first thing I think of is making sure all the tools are working right. The artistic part is what you do with them. The artistic part involves everything in this place. There’s nothing here that isn’t here for an artistic reason. That applies to the studio. The whole environment is created to be artistic. It’s my studio and it’s been this way for a long, long time, and people like it. It’s even mellowed through the years, and people are aware of that. Musicians are sensitive to that. Someone came in here only yesterday and said: ‘If the walls could only repeat what has happened here ….’”

Posted by Steve Cerra (copyright protected)

@@@@@@@@@@@

As I have previously posted a similar blog some time back I can be accused of belaboring the point. That is probably true. However, I think it is important that the reputation of a sound engineer of such prime importance as Rudy van Gelder should not be shuffled aside.

@@@@@@@@@@@

that intimidating. Somewhat humbled by the experience we head back into more populous region of the island. We decided that Rotorua and the Bay of Plenty area possibly offered the best chances for employment and, that may have been true, but the catch in the scheme was trying to find a place to live. We could not find a place to put down even temporarily while looking for employment. Staying in hotels was not an option. Despite the attractions of this heartland of Maori culture we decided that with only a few months of the sabbatical left we should head off and visit relatives in Australia. With some reluctance that is what we did.

that intimidating. Somewhat humbled by the experience we head back into more populous region of the island. We decided that Rotorua and the Bay of Plenty area possibly offered the best chances for employment and, that may have been true, but the catch in the scheme was trying to find a place to live. We could not find a place to put down even temporarily while looking for employment. Staying in hotels was not an option. Despite the attractions of this heartland of Maori culture we decided that with only a few months of the sabbatical left we should head off and visit relatives in Australia. With some reluctance that is what we did.

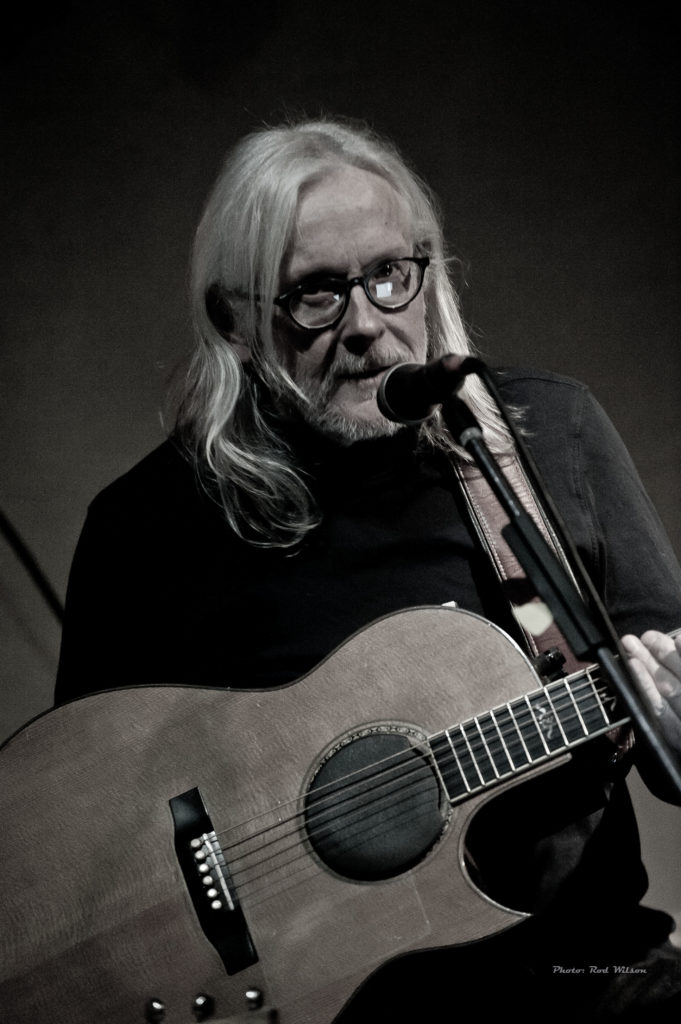

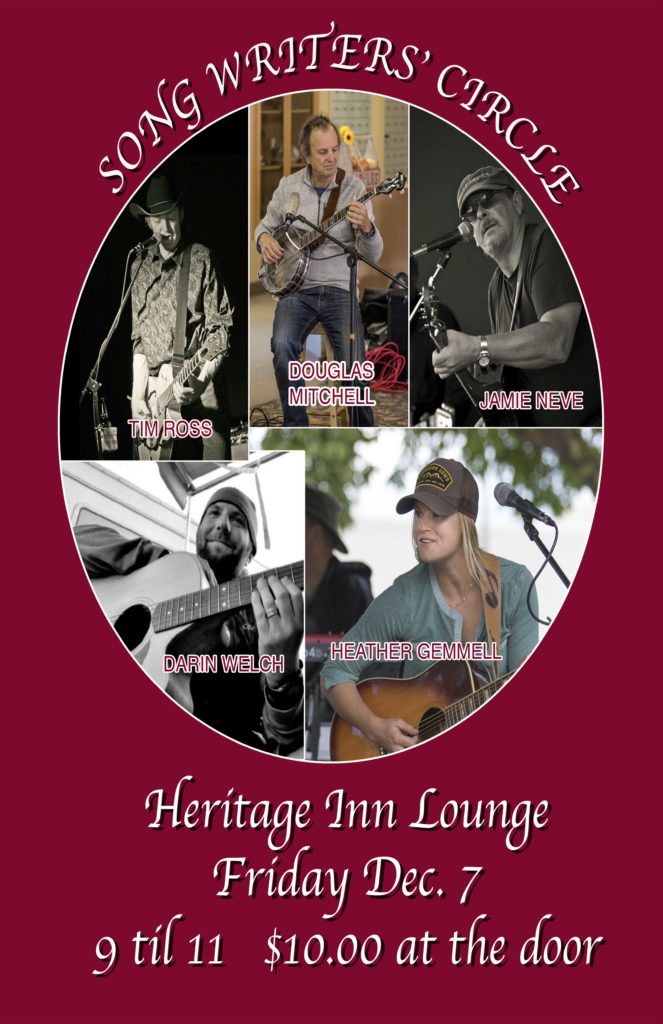

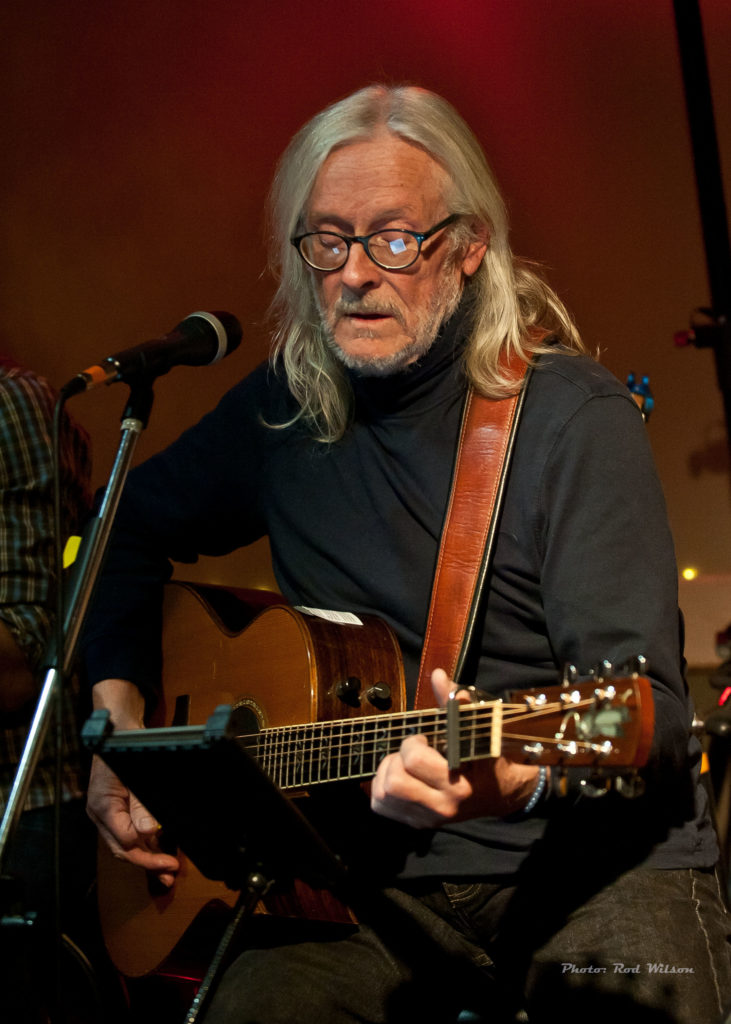

with each other before and an appreciative audience. James Neve (song writer and classic folk/rock musician) stepped away from his band The Choice to host the evening and kick off the night with a little social commentary in his song Joe Hill. If I remember correctly Joe Hill was a Swedish immigrant to the USA in the first half of the last century and was a major organizer of the Industrial Workers of the World (The IWW, other wise known

with each other before and an appreciative audience. James Neve (song writer and classic folk/rock musician) stepped away from his band The Choice to host the evening and kick off the night with a little social commentary in his song Joe Hill. If I remember correctly Joe Hill was a Swedish immigrant to the USA in the first half of the last century and was a major organizer of the Industrial Workers of the World (The IWW, other wise known  as Wobbolies). Joe came to untimely end when he was executed on November 19, 1915 in Salt Lake City Utah on charges of murder. World War I was in full swing, if that’s the right word, and at the time labor unrest was sweeping the world. Capitalist societies were running scared so it is easy to believe that the authorities manufactured a trumped up charge followed by a swift execution to get the likes of Joe Hill out of sight and out of mind. Doug Mitchell is a former educator with a tendency towards songs of social commentary. His first offering of the evening was Laughter of the Heart. Heather Gemmell is an attractive young woman with a back ground in hard rock / blues and mellow Blue Grass pickings on guitar, banjo and dobro. As an employee of the City of Cranbrook she has some responsibility for the maintenance of the the city’s parks and cemetery and that may have been the inspiration for her songs Ghost Town and Resting Place. I haven’t heard Heather perform for a while and for me her guitar picking seems to be going from strength to strength.

as Wobbolies). Joe came to untimely end when he was executed on November 19, 1915 in Salt Lake City Utah on charges of murder. World War I was in full swing, if that’s the right word, and at the time labor unrest was sweeping the world. Capitalist societies were running scared so it is easy to believe that the authorities manufactured a trumped up charge followed by a swift execution to get the likes of Joe Hill out of sight and out of mind. Doug Mitchell is a former educator with a tendency towards songs of social commentary. His first offering of the evening was Laughter of the Heart. Heather Gemmell is an attractive young woman with a back ground in hard rock / blues and mellow Blue Grass pickings on guitar, banjo and dobro. As an employee of the City of Cranbrook she has some responsibility for the maintenance of the the city’s parks and cemetery and that may have been the inspiration for her songs Ghost Town and Resting Place. I haven’t heard Heather perform for a while and for me her guitar picking seems to be going from strength to strength. Tim Ross, for the want of a better description, is an old style cowboy who has been known to rock out in the band The Bison Brothers. He is a singer/songwriter/guitar slinger who hails from Wycliffe. His day job as a natural resources consultant, which translates to “cowboy with a degree”, grants him the privilege of riding the range and making a living in the saddle. He also ranches, raising grass-finished beef. His songwriting influences range from rock n’ roll and blues to rockabilly and cowboy songs. Naturally, as a working cowboy, his song Worktime resonates with his life experiences. Darin Welch is a singer songwriter in the classic Bob Dylan / John Prine tradition and to complete the first round of the circle he offered Transition City.

Tim Ross, for the want of a better description, is an old style cowboy who has been known to rock out in the band The Bison Brothers. He is a singer/songwriter/guitar slinger who hails from Wycliffe. His day job as a natural resources consultant, which translates to “cowboy with a degree”, grants him the privilege of riding the range and making a living in the saddle. He also ranches, raising grass-finished beef. His songwriting influences range from rock n’ roll and blues to rockabilly and cowboy songs. Naturally, as a working cowboy, his song Worktime resonates with his life experiences. Darin Welch is a singer songwriter in the classic Bob Dylan / John Prine tradition and to complete the first round of the circle he offered Transition City.