It is unfortunate that for most pop/rock musicians the history of music started around 1965 and ended around 1985. There is a lot of truly great music and musicians that falls outside those parameters. One in particular is the jazz trumpeter Clark Terry . His music spanned a greater part of the twentieth century. In death he was honored with lengthy tributes in Down Beat (March, 2015) and the New York Times (Feb 23, 2015). I am sure there will be other tributes from all around the world. Here is a reprint of the Down Beat Tribute.

It is unfortunate that for most pop/rock musicians the history of music started around 1965 and ended around 1985. There is a lot of truly great music and musicians that falls outside those parameters. One in particular is the jazz trumpeter Clark Terry . His music spanned a greater part of the twentieth century. In death he was honored with lengthy tributes in Down Beat (March, 2015) and the New York Times (Feb 23, 2015). I am sure there will be other tributes from all around the world. Here is a reprint of the Down Beat Tribute.

Trumpet master Clark Terry died on Feb. 21 in Pine Bluff, Arkansas, eight days after moving from his home to a nearby hospice. He had been suffering for several years with failing health exacerbated by diabetes. He was 94.

Some of Terry’s recent activities (from 2010 to 2013) were intimately documented by director Alan Hicks in the film Keep On Keepin’ On. The documentary chronicled Terry’s decline with an unflinching honesty and lack of vanity, as he faced, among other things, amputation procedures for both legs. “I hurt all over, everywhere,” he murmured to his wife, Gwen, at one point. Through the health crises, he continued to mentor his latest protégé, pianist Justin Kauflin. The film, which was produced by Quincy Jones—yet another Terry protégé from long, long ago—debuted to great acclaim and award recognition in April 2014 at the Tribeca Film Festival.

Most musicians—trumpet players in particular—foretell their demise through their horns: shorter solos, weakening intonation, the strained high note or imprecise phrase. Louis Armstrong, Dizzy Gillespie, Miles Davis and even studio stalwarts like Harry Edison all buckled in their late years. Reluctant to give up the stage, they chose instead to devise ways of concealing and patching their weaknesses.

Clark Terry postponed that reckoning longer than nearly anyone, thanks to reserves of technique and an unquenchable optimism. Even as an octogenarian, he delivered masterful work. In 2005 I gave his recording of Porgy & Bess with Jeff Lindberg and the Chicago Jazz Orchestra a rare five-star review in DownBeat. It was a virtually perfect performance.

I saw Terry perform around the same time at the Iridium in New York City and found that it was not a mirage of post-production trickery. Though walking with a cane, Terry still played with the effervescence and elegance I remembered as a 15-year-old fan sitting a few feet from the Duke Ellington Orchestra at Chicago’s Blue Note club back in 1957. At the Iridium, as Terry’s eyesight and legs were failing him, his sound, breath control and attack seemed beyond the reach of time.

In 2008 Terry retired from performing, ending a career that spanned more than 60 years. His sound and phrasing were impossible to mistake for anyone else’s. It’s a kind of exclusivity shared by only a few trumpet players—Armstrong certainly, Ruby Braff and perhaps Edison. All had a signature sound. One could add Bix Beiderbecke, Gillespie and Davis (who is said to have studied Terry), of course, but they all became “schools” unto themselves and spawned many imitators and talented disciples. Terry owned his style so completely and protected it with such an impenetrable and subtle virtuosity that no one was capable of infringing on his territory.

“He taught so many cats,” Wynton Marsalis told me in Chicago just a week before Terry’s death. “Everybody’s been touched by him because he took his time with everybody. He carried the feeling of [jazz] with him, so when you were around him, you were around the feeling. He didn’t have to explain a lot. He just had to be himself. I’ve known him since I was 14. He’s the first person I heard who really was playing. It was the mid-’70s. Everybody was playing funk tunes. Miles was playing rock and funk, so nobody was playing jazz. But Clark Terry was playing. And no one played like CT.”

Terry was so good, so unerring, for so long, that he suffered the penalties of perfection. He was taken for granted—probably because he was never caught climbing out of a cracked note, a clumsy turn of phrase or an indifferent 12 bars. His performances were a fizz of wit and urbanity, never anguish or indecision. Worst of all, he made it all look so easy.

If he was underestimated, the last several years saw a rush to correct the record. He was named a National Endowment for the Arts Jazz Master in 1991. Readers elected him to the DownBeat Hall of Fame in 2000. The Recording Academy recognized his lifetime achievement four years ago. He even scored a hometown star on the St. Louis Walk of Fame. But surely the most direct love letter to Terry has been the film Keep On Keepin’ On. “You’re looking at the best man that ever lived,” says Quincy Jones lovingly in one scene.

Virtuosity means different things to different people. Musicians worship it when they encounter it because they understand its elusive mystery and endless process. But critics sometimes distrust it as a distraction, suspicious that a veneer of well-practiced skill may be camouflaging an emotional or creative apathy. Consistency may be admirable, but inconsistency often makes a better story. Terry’s surprises were subtle and came in oblique miniatures, easy to overlook and often undervalued. He was just so consistently brilliant, the wonders he wrought were hidden in their familiarity.

But musicians never overlooked him. One of the earliest to spot him was trumpeter Charlie Shavers, who had heard him playing in the late ’40s with the George Hudson band, a regional orchestra in St. Louis, where Terry was born on Dec. 14, 1920. As musicians do, Shavers spread the word. While making A Song Is Born for Samuel Goldwyn in 1947, bandleader Charlie Barnet asked Shavers if he knew a good jazz trumpet player. He immediately recommended Terry, who had become so captivated by the trumpet as a 10-year old that he made one of his own from a section of hose and a funnel.

“I took Charlie’s word and sent for him,” Barnet later wrote. “This was the start of a long friendship with a man who is probably the greatest trumpet player in the business. He was a fine gentleman, and he could do anything on the trumpet. … He was truly a super musician.”

Terry was not a player whose style grew and evolved in public view over the years. He hit the Barnet band fully formed and singularly distinct, becoming an instant soloist in a brass section that also included Jimmy Nottingham and a young Doc Severinsen.

On his first record date with Barnet in September 1947, his arrangement of “Sleep” was already in the book, showcasing his long, glancing phrases and sudden flame-throwing dynamics. So was his wit. He tossed off casual references to Shavers and even Harry James. On “Budandy,” his triple-tongue pirouettes contrast sharply with Barnet’s swaggering masculinity. But the best, most dazzling Terry work from the Barnet band was captured on its December 1947 Town Hall Jazz Concert, released by Columbia in the 1950s.

Terry’s singing—he called it, more accurately, “mumbles”—was an explicit extension of his trumpet phrasing, a kind of rat-a-tat scat of double talk: bubbling yet precise, with a bottled-up restraint that seemed itching to escape. It was a small sideshow among his talents that Barnet never used on a commercial record and remained something of a secret until it became familiar to audiences via The Tonight Show in the 1960s.

Only a single live broadcast from the Barnet period documents Terry’s early vocal style: a version of “The Sidewalks Of New York.” Back then, his singing was less mumbles and more straight bebop, not unlike Gillespie’s hip vocal jesting. But Terry’s vocals didn’t appear on a record until Oscar Peterson + One, released by Mercury in 1964. That album included a few Terry compositions, including “Mumbles,” featuring his vocal routine.

Shortly after the 1947 Town Hall concert, Terry (and later Nottingham and tenor saxophonist Paul Gonsalves) left Barnet for Count Basie’s band. The timing could hardly have been worse. James Petrillo, head of the American Federation of Musicians, called a strike against the record companies, shutting down the entire industry through 1948. Bookings fell off, and one famous band after another shut down.

Terry stayed with Basie through 1949, but the records from the period are not memorable. One exception is “Normania” (a.k.a. “Blee Blop Blues”) from Basie’s final RCA session in August 1949. Terry etches a stunning solo, crowded with a dry pointillist precision that had no precedent in the Basie book. It was a kind of prickly virtuosity jazz had never encountered—fluid, contained and full of Haydenesque detail. But the band was in its final months and finally broke up on Jan. 8, 1950. For Terry, though, it would only be a brief layoff. He was back in a month, this time in a Basie combo that included clarinetist Buddy DeFranco and soon tenor saxophonist Wardell Gray.

It was a transitional interlude. Terry marked his time as Basie struggled to rebuild. His trumpet was the backbone of the octet, but he soloed rarely on the few sides it made for Columbia in 1950–’51. In the DownBeat polls of the era (which reflected a time lag of several months), Terry’s name first appeared at the end of 1948, largely on the impact of his earlier Barnet work, and then disappeared entirely through the Basie period. He remained with Basie through the start-and-stop beginnings of the New Testament band in the spring and summer of 1951. Then that fall Duke Ellington beckoned.

Terry joined Ellington on Nov. 11, 1951. It had been a period of swift changes and recalibrations for the band. Alto saxophonist Johnny Hodges and drummer Sonny Greer had departed in February, taking with them two of the most primary spectrums of the band’s color scheme. Ellington might have tried a patch job. Instead, he bet on a reformation. Between March and November 1951, two men—Terry and drummer Louis Bellson—would become a wind of modernity sweeping through the band.

Ellington immediately presented Terry with what would be the first magnum opus of his career, a concert-size version of “Perdido,” a piece that had been in the book since 1941. Within six months Terry polished it to a high gloss, making it a full-dress, eight-minute summary of his entire work—a thesaurus of every lick, trick and aside in his playbook. Triple-tongued arcs flared like geysers, then leveled off, spreading into long, cool landscapes that rolled evenly across half a chorus without a breath. When he twisted a pitch or broke composure with a sudden spritz of schmaltz, it was always with a sardonic wink. Some compared him to Rex Stewart, of an earlier Ellington era. But Terry was sui generis. His playing flexed and bristled with an unforced passion wrapped in a strict sense of form and musical intelligence. When he played, his physical presence was circumscribed in a remarkably statuesque stillness, never betraying a twitch of exertion or strain in his face, lips or eyes.

“Perdido” was recorded in July 1952, just in time for Columbia to add it to what would become Ellington’s first landmark album of the long play era, Ellington Uptown, issued the following May. The band had suddenly stumbled into a new peak period, invigorated by Terry’s crackling audacity and Bellson’s barreling drive. For Terry, “Perdido” and Ellington Uptown were a career-making twosome that put him in the big time. But just as that album was released, the band moved to Capitol for an indifferent two-year period during which it was largely eclipsed by the sensational renaissance of Count Basie.

Then came the legendary performance at the 1956 Newport Jazz Festival (and subsequent concert album Ellington At Newport). Suddenly Ellington was back on top and on the cover of Time magazine. For the next three years, Terry would play to the largest audiences of his career and develop a fan base of his own. He became a fixture in a band of extraordinary fixtures: Gonsalves, Hodges, Juan Tizol, Ray Nance, Britt Woodman, Harry Carney and Ellington himself. The struggle for solo space was a competitive sport.

“Duke does have a beautiful trumpet player in the section,” Quincy Jones wrote in 1958, referring to Terry. “But he doesn’t use him enough.” Many agreed. But after the 1956 Newport fest, Ellington grew more ambitious, and Terry was well represented in the flow of new works. He became one of the first musicians to bring the flugelhorn into the jazz scene with “Juniflip” (from Newport 1958). There were wonderful odds and ends, among them “Spacemen” (from The Cosmic Scene) and “Happy Anatomy” from his final Ellington project, Anatomy Of A Murder. Best remembered may be “Lady Mac” and “Up And Down, Up And Down” from 1957’s Such Sweet Thunder.

“Terry,” wrote Leonard Feather in DownBeat in October 1957, “who has wasted the last six years playing ‘Perdido’ night after night, finally gets a couple of perfect frameworks for his witty sound and style.”

By the time he left Ellington’s band in 1959, Terry had passed Roy Eldridge and Louis Armstrong in the DownBeat Readers Poll. “Of all the men who have joined Duke Ellington’s orchestra since the great turnover in the Forties,” The New York Times’ John S. Wilson wrote, “Terry is the only one who can be considered on a level with the great Ellingtonians of the past.”

As Terry rose on the Ellington tide, other opportunities opened. He moonlighted on sessions with Clifford Brown, Maynard Ferguson, Dinah Washington and Horace Silver on EmArcy Records. He joined Thelonious Monk for the landmark 1957 album Brilliant Corners (Riverside). Monk returned the courtesy, appearing on Terry’s In Orbit (1958). And Hodges was never without him on his Ellingtonian excursions on Verve.

Late in 1959 Terry left Ellington, worked on and off with Quincy Jones, then Gerry Mulligan and Bob Brookmeyer. But Terry’s real quest was to get off the road and stay in New York. The chance came in 1960 when the major networks, after years of pressure, finally began to integrate their staff orchestras. Terry became the first African American musician to join the NBC staff.

He may have settled down a bit, but the 1960s would become his most productive decade. Nearly half the jazz recordings of his career would be done in that decade. There were reunions with Basie, Ellington and Jones, plus one-time encounters with musicians ranging from Bud Freeman to Charles Mingus, Lionel Hampton to McCoy Tyner. There was no environment in which Terry was not sought after, even advertising jingle sessions where he would often find himself sitting alongside old friends like Nottingham and Hank Jones.

It was also the decade in which Terry became widely known beyond the jazz world. When Johnny Carson took over The Tonight Show in October 1962, conductor Skitch Henderson brought Terry into the band, where he proved a natural showman with his “mumbles” scat singing. A regular feature of the show became “stump the band,” in which Carson would invite audience members to make offbeat tune requests. No request was too obscure for Terry, who would raise his hand. “I think Clark has it,” Carson would say. Terry would then mumble a made-up scat line as the other musicians nodded in mock recognition. He became the most famous sideman in America’s most famous jazz band.

When The Tonight Show moved to Los Angeles in 1972, Terry remained in New York and became increasingly active with younger musicians through a growing network of jazz educators, often recording with various student bands. He toured with a big band of his own periodically, playing festivals, cruises and other venues. (Vanguard released Clark Terry’s Big B-a-d Band Live At The Wichita Jazz Festival 1974).

Terry’s most consistent recorded output through the ’70s and ’80s was on Pablo, where the label’s famous founder, Norman Granz, regularly featured him with Basie, Ella Fitzgerald, Oscar Peterson and on his own leader projects. Terry also recorded with endless pick-up groups and rhythm sections as he traveled the world. But alongside the playful spirit and adroit craft lived a powerful blues player as well, never more so than on Abbey Lincoln’s 1990 album, The World Is Falling Down.

On the bandstand, Terry combined his formidable instrumental skills with a strong sense of showmanship. “Being able to entertain is very important,” he said in a June 1996 DownBeat cover story. “The real jazz fans may think that’s commercial—playing the horn upside-down or working with both horns at once. But the idea of playing music to an audience is to present it so they’ll enjoy it. If you don’t want to do that, you may as well rent a studio and play there. I try to pass on to young players the importance of remembering that when you’re onstage, you’re entertaining. Playing jazz is not heart surgery. You’re there to vent your feelings and have fun. We don’t work our instruments. We play them.”

Among Terry’s last important sessions were Friendship (a collaboration with drummer Max Roach) and the Porgy & Bess project in 2003 with the Chicago Jazz Orchestra. “Clark was 83 at the time we did the recording,” the CJO’s Jeff Lindberg recalled recently. “It was a big venture for him. By that time, his eyesight was quite poor, so I had to blow up the solo parts 200 percent. The long session would have been a strain to somebody half his age. But he gave it his all and got the result we all aspired to.”

Terry also had an important impact as a pioneering jazz educator. In addition to conducting clinics and workshops, he had a long stint as an adjunct professor at William Paterson University in Wayne, New Jersey. He donated instruments, correspondence, sheet music and memorabilia to the university in 2004.

Clark Terry lived a long life—with a coda that gave his many friends time to say their goodbyes. Some are movingly captured in Keep On Keepin’ On. But one special goodbye came last December. The entire Jazz at Lincoln Center Orchestra diverted from its tour route and played a special birthday concert at Terry’s hospital bedside. It was quite a concert. “We didn’t want to stop,” Marsalis later wrote on his Facebook page, “but it was time for all of us to go. But before that somber moment, we gathered around the bed and played ‘Happy Birthday’ for him. When he went to blow out the candles, he broke down. Many of us joined him. We all said goodbye and he once again recognized each individual with a touch and some kind words. … And then it was that time. What is deeper than respect and love? That’s what we felt: veneration.”

On Feb. 23, bassist Christian McBride posted a tribute on his Facebook page in which he reflected on Terry’s influence: “Every musician in the world who ever met Clark Terry is a better musician and person because of it. He now belongs to the ages.”

—John McDonough

@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@

Here is a YouTube video clip of the Clark Terry Quintet performing at Jazzwoche Burghausen 2000.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=wQAsjBkFMAo

@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@

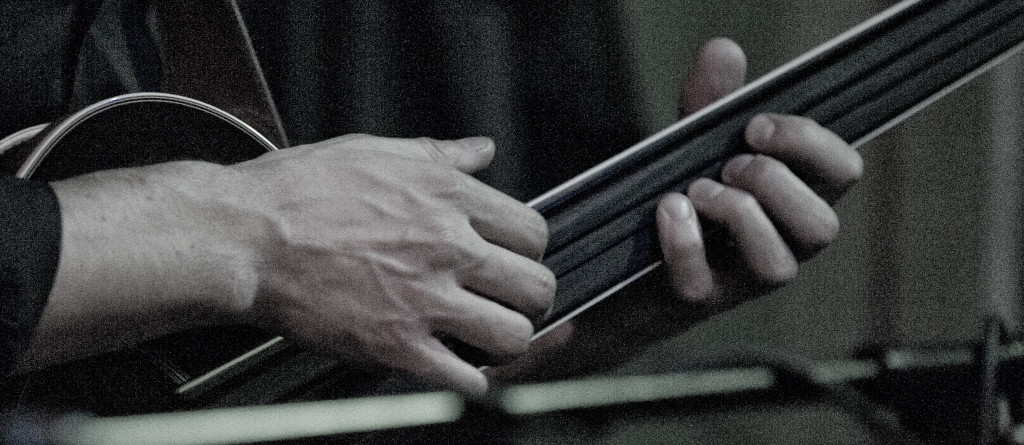

and some magnificent melodic bass solos by Stefano on a huge 6-string bass that added variety to the sonic spectrum. These four session musicians from Calgary love to play jazz and the gig here in Kimberly gave them ample opportunity to delve into a selection of songs and tunes from the Jazz Fake Book. The Jazz Fake Book, for those who don’t know, is one of several published, copyright approved, collections of a huge number of jazz standards and songs from the American Song Book. It is almost a bible for improvising jazz musician. “Want to play some tunes? What have you got in the Fake Book that we could play?” That’s pretty well how an “off the cuff” session would play out. There are no elaborated arrangements, the tunes are usually presented as an abbreviated one or two page chart that notates the basic melody, chords and possibly some brief instructions about style and tempo. Nothing is set in stone and the musicians are free to make any number of musical choices in performing the piece. In doing so, some of the “off the cuff” choices can yield some adventurous and interesting musical moments. Case in point is the quartet’s rendition of the well known I Remember April. Who would have thought that this ballad had such potential as a hard driving Samba. Thier version would be rig

and some magnificent melodic bass solos by Stefano on a huge 6-string bass that added variety to the sonic spectrum. These four session musicians from Calgary love to play jazz and the gig here in Kimberly gave them ample opportunity to delve into a selection of songs and tunes from the Jazz Fake Book. The Jazz Fake Book, for those who don’t know, is one of several published, copyright approved, collections of a huge number of jazz standards and songs from the American Song Book. It is almost a bible for improvising jazz musician. “Want to play some tunes? What have you got in the Fake Book that we could play?” That’s pretty well how an “off the cuff” session would play out. There are no elaborated arrangements, the tunes are usually presented as an abbreviated one or two page chart that notates the basic melody, chords and possibly some brief instructions about style and tempo. Nothing is set in stone and the musicians are free to make any number of musical choices in performing the piece. In doing so, some of the “off the cuff” choices can yield some adventurous and interesting musical moments. Case in point is the quartet’s rendition of the well known I Remember April. Who would have thought that this ballad had such potential as a hard driving Samba. Thier version would be rig ht at home at a carnival in Rio. Alan has a thing for the songs of Jimmy Van Heusen and and during the evening he indulged his passion with more than one Van Heusen song. The standout, of course, was Here’s That Rainy Day (from the show Carnival in Flanders) with some brilliant mallet and brushes work by Tyler Hornby behind Stefano’s extended bass solo. Some other tunes that came off the pages of the Fake Book were Somewhere Over the Rainbow, How High the Moon and the Louis Armstrong classic What a Wonderful World. Another high light of the evening was Alan’s Stride/be-bop solo version of Summertime. Despite their popularity there are some tunes that just never wear out. Summertime is one of them.

ht at home at a carnival in Rio. Alan has a thing for the songs of Jimmy Van Heusen and and during the evening he indulged his passion with more than one Van Heusen song. The standout, of course, was Here’s That Rainy Day (from the show Carnival in Flanders) with some brilliant mallet and brushes work by Tyler Hornby behind Stefano’s extended bass solo. Some other tunes that came off the pages of the Fake Book were Somewhere Over the Rainbow, How High the Moon and the Louis Armstrong classic What a Wonderful World. Another high light of the evening was Alan’s Stride/be-bop solo version of Summertime. Despite their popularity there are some tunes that just never wear out. Summertime is one of them.

.

.